I have two distinct memories in politics of things that approach a rockstar moment – a time and place where fame comes into reach; akin to when a normal person meets a musical hero. The first, disconcertingly, was outside a Conservative party conference some years ago, when I overheard two young Tory activists excitingly recounting to each other a reception they had been to the previous night where Grant Shapps! had been there!

The second was in September 2015, when Nick Gibb met ED Hirsch for the first time.

Together with Inspiration Trust, I had flown the latter to London to, among other things, give a Policy Exchange lecture. I had written to Nick Gibb’s office asking two things; if he might contribute an essay to a collection we were publishing alongside the lecture, and if he might come and introduce Hirsch on the night. By my recollection, it was a matter of seconds before an enthusiastic assent came back in reply. And now, in an empty classroom of Pimlico Academy, the two men met face to face for the first time. I do not believe that I have ever seen an expression of awe cross a Minister of the Crown’s face as much as I saw that night (though Rishi Sunak and Elon Musk the other day comes close).

Gibb had been a disciple of Hirsch for some time, of course, and had been in frequent contact remotely. As he wrote in his essay for us, he had first read his works a decade previously, during his time as Shadow Minister, and it had acted as a seminal influence on him.

That time period is worth emphasising. Eight years ago, Nick Gibb had already been involved in education for a decade.

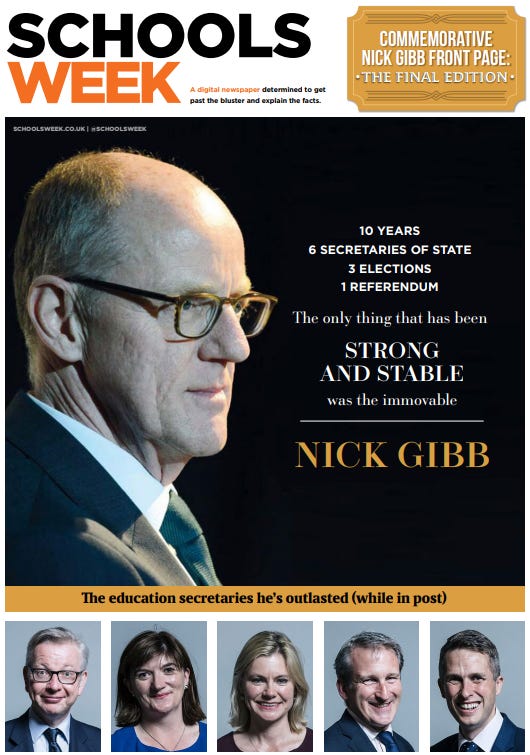

While many people joke about his lengthy tenure (on which, see this amazing thread), it is nonetheless worth dwelling on because it underpins one of the reasons for his influence. Of the eighteen years between 2005 and 2023, Nick Gibb served fifteen of them in office or shadow office. This contrasts to the other four Conservative Schools Ministers since 2010, who have served thirteen months between them (and ten of those are accounted for by Robin Walker). Lest that be seen as an unfair comparison (and for years, political historians will need to asterisk this period, not just for Covid but for political turnover at record speed), there were eight Schools Ministers under the thirteen years of Blair and Brown, and four in the five years of John Major. It’s not quite the housing merry-go-round, but it is not a constant period of Ministerial stability, either.

But tenure itself does not make a legacy. And Nick Gibb leaves a legacy of achievement – though not uncontested.

This is not the place to exhaustively debate the ways and wherefores of what his reforms have achieved. But unambiguously on his side of the ledger lies the phonics programme, embedded now within the curriculum like very few things before it. The recent international results showing that English school children are reading at a higher level than almost any others in the world at that age is an achievement which he can rightly claim much of the mantle of.

Secondly, he would cite the curriculum reforms of 2010, and their delivery not just of phonics, but of an approach inspired by Hirsch towards greater content knowledge within specifications of exams and the curriculum more broadly. This is, indeed, the thing he discusses the most – in his Policy Exchange essay, and in the magisterial interview conducted with him by TES Editor Jon Severs last year (though the headline quote is now incredibly unfortunate). If one is to synthesise ‘Gibbism’ down to anything, it is a belief in content knowledge, and against progressivism, as the guiding principle for all aspects of education – not just curriculum but the content and style of assessments; the model of teacher training; the structure of schools; and the supporting policy interventions of local and central government.

Thirdly, he would – and does – claim success for the increasingly public debate about what education evidence is, what it shows, and who can deploy it; and the greater voice of teachers in using and advancing that debate. Here, pluralism and division are a feature, not a bug. The only thing worse than teachers, academics and others debating what educational evidence does and doesn’t say, is not having that debate. It is likely that even in a counterfactual world without Gibb in office, social media and greater internet access would have brought some of this debate to the forefront regardless. But his claim to have opened the ‘secret garden’ is, I think, justified.

At this point, a wise critic would (and should) recognise the cross party nature of many of these achievements. Beneath the sound and fury which Nick Gibb generated on a personal basis, our wise critic would point to the record of the Brown government in starting to embed phonics into the curriculum, with the former Prime Minister enthused by the findings in Clackmannanshire in his native Scotland. Our critic would also cite early moves towards reform of university teacher training, and some diversity of curriculum within early stage academies, as traits which Gibb built on, rather than invented himself. Good ideas in education have many political antecedents.

Yet it is because of that cross party history that one can trace other reasons for Gibb’s legacy. It is in the nooks and crannies of the process of policymaking, implementation, and feedback, that all but the hardiest policies bloom and then wither. It is true that phonics was indeed something which the last Labour government were promoting. But it is in the careful husbandry of the idea during an extended time in Ministerial office that such policies flourish. It is the placing of phonics in Academy funding agreements, as one of the rare exceptions to curricular autonomy of these schools. It is in the steering through of the phonics screening check as a national summative assessment with published data, and an unwillingness to soften on any element of that metric. It is in the approval of funding for textbooks, and other curricular materials, that emphasise that method of reading, and the denial of support for other programmes, however well intentioned and attractive, which downplay it. It is in the scrutiny of initial teacher training programmes to ensure that the programme and evidence is passed down, faithfully, to new teachers. The nooks and crannies, where other well meaning Ministers may let things fall. Nick Gibb’s attention to detail – an accountancy mindset brought to Ministerial office – marks his legacy.

And that attention to detail in turn comes because of another reason for his legacy: genuine interest and care in the topic. As he said just the other day to the TES: “If I were doing housing, transport…I would take the same approach. But I just happened to be very passionate about education.” Like many Ministers and Shadows, the initial brief was given to him not because of any expertise. But having been granted it, it became his passion and in time, his ideological belief.

Ideology is a complex word. It is a word commonly associated with Nick Gibb, but often in a dismissive way. I am a reasoned, balanced individual, you will simply toe the party line, he is an ideologue.

But what is ideology, if not a system of belief and principle? If I had a pound for every time I had been asked, exasperatedly, why has Nick Gibb done this thing, I would be a wealthy man. But if I had another pound for every time in which I replied because he believes in it, and had been met with surprise and disgust, I would be even wealthier.

We need more ideology in politics – by which I mean we need more Ministers who believe in things, and are prepared to enact them in policy because it is what they believe. When George Tomlinson said, “The Minister knows nowt about curriculum”, he was right and wrong at the same time. The Minister probably doesn’t. The Minister probably should. And equally, if these ideas and decisions turn out to have negative consequences, then the Minister, and their party, should pay the penalty and not abdicate responsibility to the teaching profession.

And a fourth reason for his legacy, is his unwillingness to compromise.

There are many reasons why compromises happen in politics. Sometimes, the ideal solution can’t be delivered (for reasons of cost, or time, or deliverability). Sometimes, political priorities take charge. Sometimes, in the absence of clear evidence, it is easier to default to a compromise through lack of any decision. Sometimes, the feedback from stakeholders is so strong that compromise becomes desired, or required.

And all of these things can be good. Compromise is the lifeblood of politics – which is, after all, defined as the art of the possible. There are times when compromise is necessary, and times when – as Nick Gibb showed – lack of it is not principle, but in fact stubbornness. A tree unbending in a storm is good, until the point where lack of flexibility makes it snap and fall.

But Ministers can sometimes also be prepared to compromise too quickly. If one is giving a speech, one prefers, of course, not to be heckled. Compromise can mean that hard choices can be denied or deferred. Compromise sometimes brings with it the sugar rush of being garlanded by stakeholders with being prepared to take the right decision regardless of starting point. Nick Gibb – that shy, quiet, softly spoken man – was nevertheless prepared to take on and explain his positions, when many other politicians would have ducked it. Don’t look now, Danny, but you’re standing up and making an argument.

This legacy comes at a cost. His record is by no means without blemish. He was, on occasion, too reticent about seeking out opposing views, or changing his mind in response to those who had a good point but came from what he felt was an ideological place of difference. Too many issues which fell within his purview are nowhere near where they should be in 2023: school funding, teacher supply, wider children’s services. To those who protest in his defence that they are above the pay grade of a sub-Cabinet Minister, one cannot have it both ways. If he can be credited with an outsized influence to that of a typical junior Minister, so too can he blamed for the failures during this last decade (and he himself admits this).

And while he has won many arguments – and gained the respect of many within teaching and education more broadly who have never and would never vote Conservative - he has also made implacable opponents. Like his former boss Michael Gove, a seeming desire on occasion to cross the street to start an argument paid some dividends, but ultimately brought penalty too.

His time in office was about making choices. He will stand by those choices, but they were not choices everyone would have made, and he will own that whole record, good and bad.

But the reason the system will miss him is ultimately less about these choices, impactful as they were, but instead more his sustained oversight of the system, and care for the policy area. I like much of what he did, on a principled basis. But I would admire equally someone from a different educational tradition who similarly devoted their career to this; who could use, for example, Labour’s forthcoming curriculum and assessment review to bring in a wholly different system which they too maintain and nurture for a decade or more, and seek to shape other actors around it.

But I fear that the combination of circumstances that allowed Nick Gibb to stay so long in post – someone devoted to a policy area; someone with lack of ambition for higher office or desire to “become famous, sell books, or go on ‘I’m A Celebrity’”; and successive Prime Ministers prepared to keep a high profile brief unavailable for patronage elsewhere – will come about all too rarely. It may be some time before we see his like again.