The most popular government education policy that you’ve (probably) never heard of

“Yeah, I think that’s really good. Especially if it’s free because it costs quite a lot of money [ to do it privately]. But yeah, I think…

“Yeah, I think that’s really good. Especially if it’s free because it costs quite a lot of money [ to do it privately]. But yeah, I think when they go back and they do get assessed and if they did need the extra support, I think that’s brilliant”

“I’d bite their hand off.”

“I’d sit next to her in front of the computer for this, whenever it was. Whatever it takes.”

It’s rare, when doing focus groups, to come across something this powerfully endorsed. But that’s what we heard across a number of groups which Public First ran, last week. We were discussing tutoring, and the government plans to roll it out for young people falling behind.

But we also heard this:

[having nodded along strongly as NTP was described] “I’m just a bit shocked that you say that. So I’ve never heard about that. How, I mean, is that something that has been out? Has it come out in the media?”

When asked, not a single participant had heard of NTP, or even knew that the free tutoring was happening.

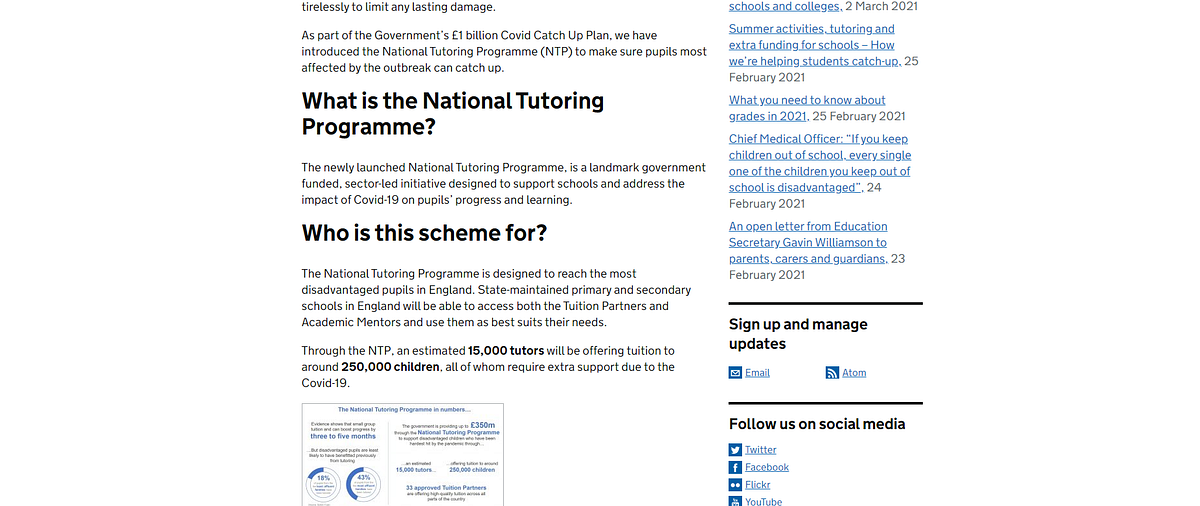

This is probably surprising to those who work in education. You certainly have heard about tutoring plans, and government plans for catch up, including £1bn of funding, with the new National Tutoring Programme at the heart of it.

But it turns out that parents aren’t that aware of it.

Partly, it’s that it’s early days for the scheme — launched during a period when most children are at home, not in school. But I also think it speaks to a wider issue about how the Government manages communications in education.

Look at this screenshot, for example. This is from the main DfE blog announcing the launch of NTP. It talks about NTP, but entirely from a sector perspective. The purpose of it is to “support schools”. That’s an interesting turn of phrase. I would have thought it was to support children and young people.

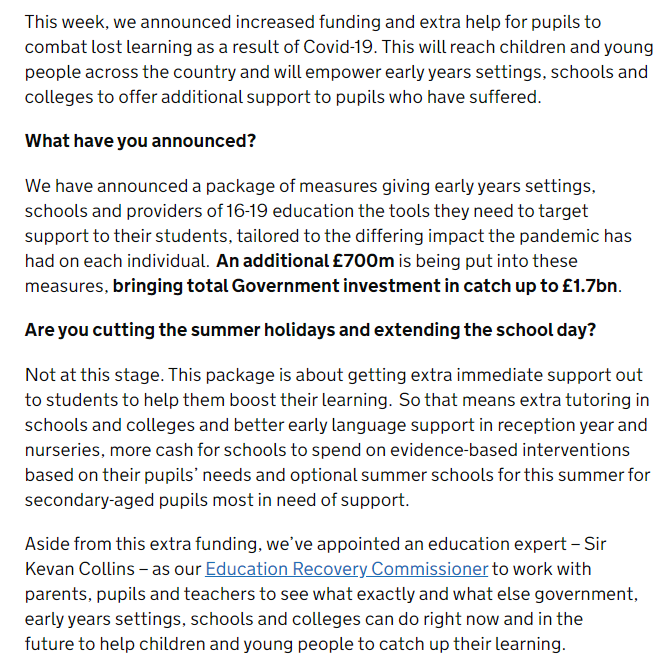

Here’s another page from the DfE explaining how NTP works. The £700m-£1.7bn has been given to education settings, the information makes clear. Here, at least, it talks about how schools can be used to get this money out to students — but again the focus is on how “early years settings, schools and colleges can be empowered to offer additional support”. All the agency is with providers. Parents and children are the passive recipients.

Now, obviously, DfE does need to communicate with school leaders and teachers — including a whole lot of technical information and guidance about funding flows, how they can be accounted for, what they can be spent on, and the like, including on NTP. But Government also needs — and I would argue strongly that it doesn’t have — an equally well develop and prioritised communications message to parents about tutoring. Tutoring is, after all, for children. The schools and other settings are simply the commissioner.

There are some isolated examples I’ve found where the DfE tries to do this — further down the same page in the example quoted above — though even here, it is only unambiguously a parent facing answer for the first paragraph before it veers off into technical explanation of funding streams available for schools and what they, schools, should do.

DfEs track record of direct communication to parents is patchy. As a brand, it doesn’t have that much parental visibility — and it certainly doesn’t have anywhere near as much trust to parents and children as local schools. (This is, incidentally, a significant weakness for the DfE when they’re trying to engage in small p and big P political debates over issues like funding, and teacher workload. But that’s a whole different blog). But where the DfE has done direct parent comms — as in the examples here, from the ‘back to school’ campaigns in the summer ahead of last Autumn’s reopenings, my understanding is that the internal data reported back very positively in terms of shifting parental behaviours and attitudes. (Though note that the DfE brand and name doesn’t appear anywhere directly in these, almost certainly deliberately — the branding is NHS and HM Government).

But just because it’s difficult doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be done. In fact, I would argue that the reason it hasn’t been done in anything like a systematic way is that it betrays the fact that often, from a DfE perspective, children and parents are a secondary audience. The main success metric often appears to be teachers and heads being aware of DfE’s announcements, and taking actions in response to them.

Now — again — I’m not saying this isn’t important. But as my colleague Rachel Wolf has long argued, parents being neglected as stakeholders has significant risks for government from a policy level and from a political level. The views of parents ought to be front and centre of DfE decision making — even when it makes things slightly more difficult for the Department.

NTP itself, as an organisation, is correctly thinking through its own communications and how it becomes more visible to parents as children and young people return to schools, and I’m delighted that they are. But it is a small and new organisation. The only way this programme is going to be known about by parents at scale is through the amplification of central government messaging.

What does that mean for NTP? Well, another thing you’d expect me to say is that the messages need to be tested — as I’m sure the reopening ones were. But it almost certainly means exploring messages like the following:

When your child returns to school, speak to their teacher or their headteacher about any additional support they might need — including whether they might benefit from free 1:1 and small group tutoring delivered through your school.

The Government is funding free 1:1 and small group tuition for young people who need extra support. If you think your child might benefit from this, please speak to your school.

Pupils will be entitled to an average [x] hours of 1:1 and small group tuition, free of charge, to help support them in subjects where they need extra help. Please ask your school for more information or see here www.gov.uk/tutoring.

The Government has announced a new National Tutoring Programme. This means that your child may be entitled to free 1:1 or small group tutoring, arranged through their school and delivered by external trained tutors. If you think your child would benefit from this, please speak to your school.

As part of supporting all children as they return to schools, the Government is spending more than £1bn to ensure that 250,000 children can receive up to x hours of 1:1 and small group tutoring to help them catch up. Your child’s school and teacher will let you know if your child might benefit from this — or please discuss it with them.

In all of these, the parent and the child is front and centre. The school are clearly the decision makers — parents don’t have the right to demand tutoring. But this is, after all, a programme aimed at them — their children — and funded by government, with schools acting as the trusted advisers. These messages, then, places all the actors where they should be. The Government is the funder. The school is the broker, and the trusted expert. The parents and children are the beneficiaries, but parents are also — vitally — a co-creator in the conversation about whether tutoring may benefit their child.

This isn’t just about the wording on the DfE’s blog. It’s about Ministerial speeches, references in No10 press conferences, MP newsletters and updates to their constituents, social media videos, and pooled TV clips to the camera when every politician from the Prime Minister down is visiting schools and settings and speaking to the media for the evening news.

Tutoring won’t work unless all parties — the school, the tutoring company, and the student — are committed to it. But the danger is that at the moment, the focus is tilted too much towards the delivery mechanisms. The Government has invested significant amounts of taxpayers’ money in catch up, with almost certainly more to come. It will be expecting a dividend in policy terms — and also political terms. If parents keep on expressing bafflement as to what this measure is, then government will have failed.