(Tuesday) thoughts: Two and a half cheers for England in PISA?

If one spends much time in UK education policy discourse, you hear a number of things stated as fact. England has a vastly unequal education system. Our long tail of poor performance is one of the reasons for our inequity. More equal countries such as Finland do much better and that’s what we should seek to replicate. It’s good that Scotland and Wales have moved away from sharp accountability, and when will England follow.

Which is why it’s so interesting that today’s PISA results cast, at a minimum, a real doubt on so many of these.

Although the headline scores for all the home nations’ 15 year olds have fallen since last time, they more or less mirror the OECD wide falls due to the pandemic (though it’s worth noting that high performing countries still managed to improve scores over this period). The net effect is that England has risen in the rankings compared to last time; part of a consistent rise over the past 14 years since 2009. England now scores 11th in maths, 13th in reading, and 13th in science.

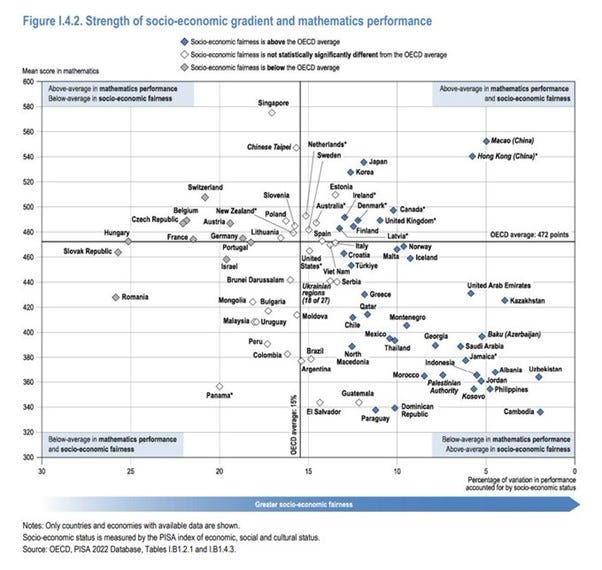

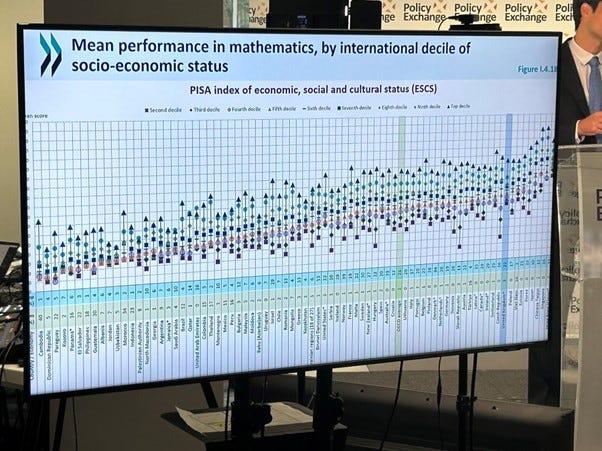

The OECD also conclude that the UK is now in the ‘golden quartile’ where performance is above average AND socio economic equity is above average. This is “where the UK wants to be; where all education systems want to be” according to the summary presentation given today. No European country is performing better within this quadrant.

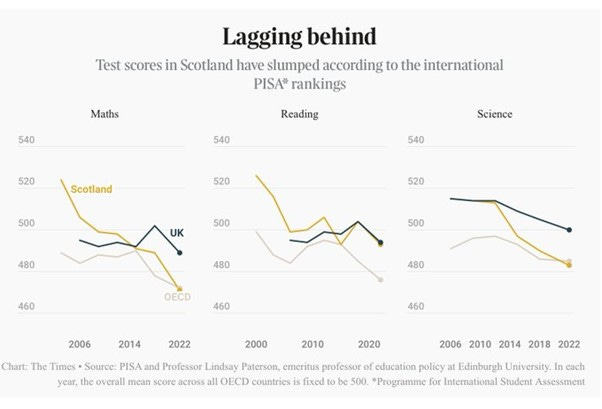

Finland, long beloved of people who want more reindeer and less Ofsted, is now performing below the UK – and, more significantly, today’s results show a continuation whereby Finland has been declining in maths since 2006 and also in literacy since 2006. The Finnish slide has been known for a while but much denied.

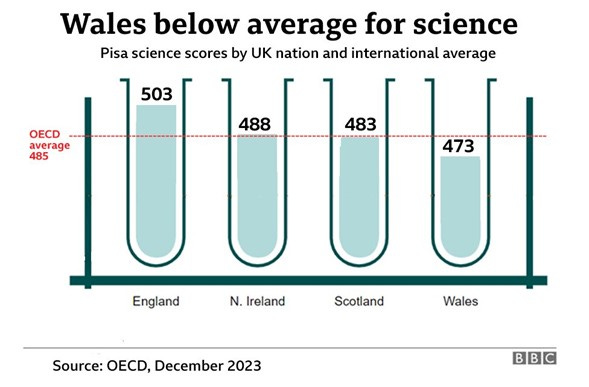

And Scotland and Wales have really performed poorly. PISA doesn’t ascribe causation to these falls, but the intra-UK policy differences do form something of a natural experiment, and it’s hard not to conclude that at least some of the reason for this discrepancy is different choice made on curriculum, assessment and accountability by our Celtic neighbours.

And – with some caveats – the inequity by socio economic status is also shrinking and below OECD average. The caveats here reflect the fact that England had fewer students take the test than is ideal, so statistically there is a possible overstatement of up to 8 points – and this is most likely to be seen when looking at lower performers and poorer students, who were less likely to take the test. Nevertheless, PISA today judged that the UKs performance in maths has “quite a compressed distribution”.

I find it fascinating, therefore, how begrudging some of the responses have been. Of course, not all the findings are good – and some of them are pretty shocking. We have a lot of hungry children - more than almost anyone else in the OECD – and that’s shameful. Children’s life satisfaction is almost the lowest in the OECD, which is also worrying and should be a priority to address. And it’s true, as Christian Bokhove has said, that PISA results are a starting point not an end point for conversations.

But come on. If one simply read some of the statements from ASCL, EPI and others, as well as media coverage this morning, you’d be forgiven for thinking they were describing a totally different set of results. Of course the Education Secretary is going to ramp up the results – that’s politics. (It’s also politics, albeit politics that has now come back to bite them, for the Tories to have briefed how terrible PISA is as an indicator for the past few years).

But it’s equally grating to see press releases and statements that seem to go out of their way to draft away the progress that has been made, on the grounds that they don’t seem to want to give the government credit.

Today’s results are both a pretty strong, albeit not universal, justification of what the English government has done in education policy and maths policy for a long time. Importantly, this isn’t a party political point; a lot of the groundwork was set out by Labour as part of a thirty year consensus as to how we should design and oversee schools. And most importantly, it’s justification for the work of teachers and leaders across the system that have taught these 15 year olds within the framework designed and overseen by successive governments.

So if this is the start, not the end, of a conversation (or in reality, the continuation of a conversation), what are the main lessons for Labour? I think there are four:

Firstly, focus on variation within schools, not between them. Sam makes the very good observation that today’s PISA results are less indications that we have a school improvement challenge (though there of course remain underperforming schools that we need a solution for), and more about consistency of performance within schools, when it comes to maths (and this replicates findings elsewhere in other subjects). This is something that often eludes government because it’s about day to day educational practice and not policy prescription, but classroom consistency should be a priority for the next government.

Secondly, Labour should absolutely stay the course on what maths improvements any government should do. I’m much in favour of maths to 18, but a huge change to 16-18 curriculum and assessment is really not the way to go about it. A focus on primary maths – and the less glamorous but even more important aspect of Key Stage 3 maths – is what is needed. David Thomas of MESME summarises good maths findings here from today.

Thirdly, Labour are completely right to be focusing on things going on outside the school gates. PISA shows us that we do need to prioritise these out of school interventions, not just to go up the rankings but also because that’s a core part of what it means to grow up well, and we are terribly far behind where we ought to be as a wealthy OECD country.

But fourthly, this focus on out of school outcomes shouldn’t mean going backwards, as an act of policy or more likely accidentally, on key aspects of the last fifteen to twenty years of schools policy. Don’t just nod along to education shibboleths. It turns out Finland isn’t all that. And it turns out that in an Anglophone context, loosening the reins on accountability leads, as per Scotland and Wales, to some pretty poor outcomes, even if it means teaching unions cheer you. There are different directions in which Ofsted reform, and a curriculum review – to take two practical things which Labour are going to look at – can lead. To me, PISA shows pretty clearly which one has promise, and which one has peril.